Ethical dilemmas surrounding patients´ “unwise” treatment preferences and suboptimal decision quality: case series of three renal cell carcinoma patients who developed local recurrences after non-guideline-concordant care choices

Khalid Al Rumaihi, Nagy Younes, Ibrahim Adnan Khalil, Alaeddin Badawi, Ali Barah, Walid El Ansari

Corresponding author: Walid El Ansari, Department of Surgery, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

Received: 25 Oct 2023 - Accepted: 04 Oct 2024 - Published: 18 Oct 2024

Domain: General surgery,Surgical oncology,Urology

Keywords: Cryoablation, guideline-concordant therapy, patient-centered medicine, partial nephrectomy, renal cell carcinoma, shared decision-making

©Khalid Al Rumaihi et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Khalid Al Rumaihi et al. Ethical dilemmas surrounding patients´ “unwise” treatment preferences and suboptimal decision quality: case series of three renal cell carcinoma patients who developed local recurrences after non-guideline-concordant care choices. Pan African Medical Journal. 2024;49:45. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2024.49.45.42047]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/49/45/full

Case series

Ethical dilemmas surrounding patients´ “unwise” treatment preferences and suboptimal decision quality: case series of three renal cell carcinoma patients who developed local recurrences after non-guideline-concordant care choices

Ethical dilemmas surrounding patients´ “unwise” treatment preferences and suboptimal decision quality: case series of three renal cell carcinoma patients who developed local recurrences after non-guideline-concordant care choices

Khalid Al Rumaihi1,2,3, Nagy Younes1, Ibrahim Adnan Khalil1, Alaeddin Badawi1, Ali Barah4, ![]() Walid El Ansari2,3,5,&

Walid El Ansari2,3,5,&

&Corresponding author

Patient engagement and shared decision-making (SDM) between patients and clinicians is the foundation of patient-centered care. It aims to reach a treatment option that fits the patient's preference and is guideline-concordant. We sought to evaluate the possible causes and outcomes of patient's non-guideline-concordant care choices. Using a retrospective analysis of the medical records of patients who underwent cryoablation for small renal masses between January 2010 and January 2023. Inclusion criteria were patients with renal tumor(s) who underwent cryoablation which was not recommended by the multidisciplinary team (MDT). We present three patients with unilateral clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Based on imaging and other findings, the oncology MDT recommended partial/radical nephrectomy. Upon consultation, each refused surgery and preferred cryoablation. Respecting their choice, cryoablation was undertaken. The patients had treatment failure and developed recurrences that could have possibly been avoided with guideline-concordant care. Shared decision-making in healthcare involves several aspects: patient/family; uncertainty of available evidence of various treatments; MDT meetings; and treatment team. For patients to select 'wise' treatment preferences i.e. guideline-concordant care, multi-layered complex intellectual and cognitive processes are required, where experience may play a role. Healthcare professionals require guidance and training on appropriate SDM in clinical settings, and awareness of tools to solicit patient choice to guideline-concordant care whilst observing patient autonomy. Patients and treatment teams need the capacity, knowledge, and skills to reach a 'wise' guideline-concordant care treatment preference jointly. Patients' unwise preference could lead to suboptimal outcomes, in the case of our patients, tumor recurrence.

Treatment decision-making processes pass through three stages: information exchange, deliberation, and deciding on the treatment to implement [1]. Effective patient-healthcare provider communication promotes the awareness and appreciation of patients to their illnesses, available treatment options, and adherence, which is essential for managing the condition [2]. Patient engagement (PE) and shared decision-making (SDM) between the patient and clinician (s) is the foundation of patient-centered care, premised on a respectful dialog where the patient's preferences and knowledge of the physician interact to generate an optimal decision [3]. Hence in SDM, healthcare professionals (HCP) and their patients together have to decide upon the treatment option that best fits the patient's situation and preference [4]. By improving their relationships with patients, HCPs can enhance SDM [5].

A body of literature suggests that such notions are associated with better outcomes. For instance, for the treatment of depression, PE in decision-making was associated with the receipt of more adequate treatment, guideline-concordant care, and satisfaction [6,7]. Patient preferences are viewed favorably, to the extent that recent mental health law reforms in the UK prioritize patient choice [8]; and in the USA, approaches to prenatal care delivery incorporate patient preferences [9].

But patients might not be prepared to engage in SDM, or desire to be fully involved [3]. Patients with carpal tunnel syndrome had varying degrees of involvement in their care decision-making, preferring a semi-passive role in their intra/postoperative decisions [10]; and for vascular diseases, SDM remains low [4]. In addition, patients might be at risk of suboptimal decision quality: breast cancer care is characterized by preference-sensitive decisions where no single choice dominates, and the management approach is guided by patient values/preferences, but due to the complex choices, patients might be vulnerable to suboptimal decision quality, such as the timing of adjuvant radiation with regards to its toxicity, cosmetic effect, and oncological outcomes [11].

In such cases, the perceptions of patients and clinicians might not be congruent, raising the question of what happens when the patient's and physician´s views do not align [12]. For gynecological cancer care, the perspectives of patients and clinicians aligned on many topics but diverged on others [12] If one assumes that the practitioner is right (a subject of research in itself), then how do we get the patient to follow that advice [13]? A high-quality, patient-centered decision involves an accurate understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment options, as well as concordance with the patient's preferences [11].

As for the treatment of clinically localized renal masses, the four major management strategies available comprise radical nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy (PN), cryoablation (CA), and active surveillance. Each management strategy is associated with a unique profile of functional and oncological outcomes. The choice of the management modality that suits the patient depends on tumor characteristics such as size, complexity, and nature (whether cystic/solid), along with patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and renal function [14]. The multiple treatment options and factors that influence the choice of the best treatment modality highlight the importance of an oncology multidisciplinary team (MDT) in such cases.

We present a retrospective analysis of three non-consecutive patients diagnosed with unilateral clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). For each patient, based on imaging and other findings, the oncology MDT recommended partial/radical nephrectomy. However, upon consultation and counseling with the patients, each refused surgery and preferred cryoablation. Although healthcare in Qatar is universal and free of charge, eliminating financial factors that might direct patients toward lower-cost treatment modalities, cryoablation was undertaken in keeping with the patient's choice of treatment. However, the three patients subsequently developed recurrences. The specific objectives are to: a) describe and outline the cases; b) highlight that the cases chose non-guideline concordant care; c) explore the possible reasons why the cases made such choices; d) discuss the processes, discourses, and implications of such choices; and, e) emphasize some useful available tools that healthcare professionals can use to assist patients in making guideline-concordant treatment choices.

Study design: a retrospective analysis of the medical records.

Setting: Department of Urology, Uro-Oncology Unit, Hamad Medical Corporation in Doha, State of Qatar.

Cases: three non-consecutive patients who underwent CA for small renal masses during the period January 2010 to January 2023 at our institution and subsequently developed recurrence.

Variables: we retrieved demographic (age, sex, nationality, medical history, comorbidities, socio-economic status, education, occupation), radiologic (imaging modality, date done, laterality, tumor size, tumor nature, nephrometry score, tumor stage), MDT recommendation) and other relevant cryoablation (date, number of needles used, gas used, number of freezing cycles, biopsy results, tumor grade) data.

Data sources/measurement: we used hospital electronic databases and medical imaging databases. In addition, we also gathered from the databases any available socio-demographic data and/or medical history information that could aid in explaining the potential reasons behind the non-guideline-concordant care choices that these patients selected, as well as assist in the patients´ judgments and processes for refusing surgery. These variables included age at procedure, sex, nationality, medical history and comorbidities, socioeconomic status, education, and occupation.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: the inclusion criteria were all patients with renal tumor (s) who selected and underwent CA despite that it was not recommended by the MDT. Cases that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Statistical methods: we sought to qualitatively evaluate the possible causes and outcomes of non-guideline-concordant care choices. Hence, no statistical analysis was required or undertaken.

Counselling and patient choice at our institution: during the counseling, any MDT decision was thoroughly discussed with each patient in his/her native language or with an interpreter where required, highlighting that the recommended intervention is beneficial for the patient's health. In addition, patients were provided with a set of useful educational electronic internet links. The details of the proposed surgical treatment with its expected outcomes, benefits, and possible complication (s) were meticulously discussed and reviewed with the patient. Other available alternative treatments (e.g. ablative treatments, active surveillance) [14] were also deliberated with the patients, again each with its excepted outcomes, benefits, and possible complication (s) and their probabilities. For instance, counseling patients about PN versus CA in the management of renal masses includes clarifying the higher risk of local recurrence and lower oncological outcomes of CA compared to PN. However, CA is associated with lower perioperative complication (s) and better preservation of renal function. Patients are then given one week to think and reflect on the information provided and receive a second opinion if patients wish to do so. Patients were encouraged to return if they had any queries, concerns, or uncertainties; and to arrange and schedule the treatment modality that they select.

Multidisciplinary team membership: consisted of senior consultants in uro-oncology, medical oncology, radiology, interventional radiology, and histopathology.

Cryoblation technique: the procedure is performed in the prone position under general anesthesia using an angio-CT suite. A planning triphasic CT scan is performed to outline the lesion, and a core biopsy is taken from the renal tumors using a coaxial system 18G x 16cm biopsy needle at the beginning of the procedure before the start of CA. Additionally, a coil marker is placed into the lesion through the already placed co-axial needle. A 16G CA needles are placed into the renal lesion the number of needles is changed according to the tumor size to make sure that the whole renal lesion is included in the CA ball. Cryoablation using Argon gas is started for 10 minutes followed by passive thawing until the temperature reaches 0° Celsius which is followed by a 2nd cycle of CA for 10 minutes followed by active thawing using Helium gas until the temperature reaches 30° Celsius and then the needles are removed.

Follow-up post cryoablation: periodic medical history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and pre-and post-contrast abdominal imaging within 6 months (if not contraindicated) [14], subsequent follow-up is scheduled according to the MDT recommendations.

Ethical consideration: informed consent was obtained from the subjects involved in the study.

Definitions

Patient engagement (PE): the desire and capability to actively choose to participate in care in a way uniquely appropriate to the individual, in cooperation with a healthcare provider or institution, to maximize outcomes or improve the experiences of care [15].

Shared decision-making (SDM): an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences [16].

Optimal treatment strategies: the decision rule that leads to the most beneficial outcome on average or the greatest value [17].

We found a total of 3 cases with renal tumors who preferred CA treatment despite that MDT recommended partial/radical nephrectomy.

Patient socio-demographics and diagnosis: patients´ age ranged between 56 to 68 years and the sample comprised two males and one female. All three patients underwent percutaneous CA as described above. Table 1 lists the particulars of the patients´ socio-demographics, MDT plan, and original tumor characteristics. Figure 1 depicts the investigations and diagnosis of the initial renal masses of the three patients.

Tumor recurrence: tumor recurrence was detected on follow-up imaging. The mean duration for tumor recurrence was 30.6 months. Recurrence was managed by redo-cryoablation in patient 2 and patient 3, while patient 1 omitted management of recurrence as he was diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer. The characteristics of tumor recurrence are listed in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 2.

"No decision about me, without me"

With person-centered care, patients take substantial roles in decision-making [18,19]. Patient engagement is essential for quality care and patient safety [18] and works by transforming new knowledge and values into behaviors [20]. The current report provides insights into the complex ways patients make decisions and engage in selecting their treatments. We presented three clear cell RCC cases where patients practiced their preference and unfortunately selected non-guideline-concordant care, contrary to their HCPs' recommendations, with treatment failure and recurrences that could have been avoided should they have selected guideline-concordant care.

Shared decision-making comprises dialogue, where patient's preferences interact with the physician's knowledge to reach optimal decisions [3]. Shared decision-making in healthcare involves four aspects: the patient (and family); prevailing uncertainty of the available evidence for various treatment options; the dynamics of MDT meeting (s); and the treatment team. Patients need to have the capacity to process complex information and treatment options and make decisions in their best interest. Healthcare professionals need to have the capacity to lay out the necessary information to assist patients in making 'wise' choices, and the capability to advise them when they select non-guideline-concordant care that could result in suboptimal outcomes. Uncertainty of the evidence adds more complexity as potential outcomes of treatment options are expressed in probabilities and likelihoods.

Potential reasons for refusing surgery and preferring cryoablation: the MDT decisions were PN (patient 1) and radical nephrectomy (patient 2 and patient 3). The outcomes and possible complication (s) were clarified to the patients. In Qatar, healthcare is free, hence the financial burden of the treatment options is not a determining factor of the selected choice (no out-of-pocket expenses). The patients refused surgery due to possible complications (bleeding, cosmetic effects of scars, visceral injury, renal function deterioration, etc.) [14]. They preferred CA although it was not the MDT-recommended intervention possibly due to the tumor´s location, cystic nature, and size. Still, CA has a higher risk of treatment failure and recurrence [14,21].

Patients and decision-making

Unwise decision-making poses ethical challenges for physicians and would reappraise a patient´s capacity if she/he presents with such a decision [22]. Ethical care builds on beneficence and nonmaleficence [23,24], and HCPs are contested when patients present with suboptimal decisions [25]. Patients´ health literacy and numeracy influence their decision preferences [26], or they might not desire to make decisions, choosing to trust the physician [27-29], particularly when physicians provide reasoning [30-33], entrusting them with final decisions [34].

Regarding patient capacity, Table 1 shows that patients 1 and 3 were of middle/upper socioeconomic status, well-educated, and employed in intellectual jobs. This suggests that, provided with information about treatment options and outcomes, both patients could make optimal decisions. It is difficult to speculate the reasons behind a choice that a patient makes, however, patient 1 had a history of several surgical procedures: rectal cancer (2008) resected but complicated by incisional hernia, tumor recurrence, and intestinal obstruction; exploration laparotomy, ileostomy, hernia repair (2009); ileostomy revision and recurrent hernia repair (2011); then right renal mass and offered partial nephrectomy (2017). Such a surgical history might have influenced his decision-making away from the surgical option to ablation despite its lower success rate [35,36].

On the other hand, patient 3, being female, might have preferred ablation for aesthetic reasons (lack of visible surgical scar). Conversely, case 2 was a car mechanic with a high school education, and no history indicators to provide clues to his non-guideline-concordant choice. He might have believed that surgery could affect his job which requires physical fitness. Our findings concur with that socio-demographic features e.g., being female and greater educational attainment, higher health literacy/numeracy, and disease severity influence the extent to which patients desire active involvement in care decisions [26,37].

A chosen preference might be explained by its benefits and negative consequences. Different options have their risks (probability of adverse outcomes) and benefits [3,4], and patient preference builds on their perceptions of these [38]. Patients value the use of personalized risks when deciding treatment [39], and their decisions relate to the perceived benefits and negative consequences [40]. Ansari's paradox suggests that for individuals to perceive favorable or very favorable cost-benefit ratios, their perceptions of benefits needed to be 62%-82% more than the negative consequences [40]. Social exchange is the actions of individuals motivated by the expected returns [41]. Hence, our patients were more likely to choose guideline-concordant care if they perceived its benefits to be considerably more than its negative consequences. However, the benefits and negative consequences of treatments are premised on complex estimations, interactions between clinical evidence of variable quality, and patients´ appreciation of such evidence. Although uncertainty should be disclosed, in cancer treatment decision making, uncertainty was disclosed in only 34% of consultations [39].

Available evidence, probabilities, and certainty

For our patients, evidence suggests the postoperative complications were more for PN vs CA (42% vs 23%), albeit CA has higher local recurrence [21]; and compared to PN, CA for cT1 renal tumors yields inferior results [36]. There seems no consensus on the criteria to select the best patients, although due to the higher rates of CA treatment failure, it is seldom offered to patients with less comorbidities and good life expectancy [42]. Ablation may have worse local recurrence and metastasis outcomes [35], with increased mortality among patients with pT1b RCC [43]. Patients should be counseled on such increased odds of tumor persistence or local recurrence after ablation compared to surgery [14].

The main challenge for care teams is that it is impossible to point out the patient who would benefit. Our three cases selected ablation, and despite being non-guideline concordant, there was no absolute certainty that any of these patients would develop a recurrence, only a likelihood. Hence, preventing a recurrence by selecting a guideline-concordant option is not guaranteed. Such a “prevention paradox” highlights that prevention strategies offering large health benefits might realize fewer benefits at an “individual” level. A preventive measure that brings large benefits to the community may offer little to most participating persons [44]. There is no single “correct” or “best” management plan; rather, more or less “reasonable” or “defensible” plans [45].

Multidisciplinary team meetings

Multidisciplinary team meetings represent the backbone of clinical management [46]. Our patients were discussed at the MDT meetings; hence they were more likely to receive more accurate and complete pre-operative staging and better accordance with clinical guidelines for treatment, thus resulting in better outcomes [47,48]. However, cancer care is continuously challenged due to contemporary management regimes, multi-modal therapies, and survivorship issues [46]. Traditionally, patients are not physically present at MDT meetings, and there have been calls that patients be actively integrated into MDT processes to ascertain they have informed choices and ensure that recommendations are premised on the best available evidence [34].

Multidisciplinary team meetings are most beneficial when patient choice prevails, but patients are usually seen after the meeting [49]. Barriers to the implementation of MDT suggestions encompass not considering patient choices [50]. Bladder and prostate cancer guidelines [51,52] do not recommend using synchronous joint clinics, despite that most patients seen in synchronous joint uro-oncology clinics preferred joint consultations [49]. Given the information complexity, HCPs' roles necessitate skills and tools for patient-centered communication and visual displays [53]. Shared decision-making can be enhanced by HCPs skillfully aiding their patients to debate their options [4].

Physicians and skill sets: from the physicians' side, the patient-centered approach respects patient preferences to steer clinical decisions [54]. However, HCPs have little guidance on how to accomplish this [55]; and clinicians might be poor at judging patients´ treatment preferences [56]. Patients' preferences require clear information from HCPs [57,58], and HCPs need to appraise whether the patient understood the options, e.g., by asking the patient to repeat or paraphrase the options [59]. Explanations to patients of the links between a selected preference and resultant outcomes help them make informed decisions, and we undertook this with our patients. Skills for effective SDM are not taught in medical schools. In Holland, SDM was low due to unsatisfactory patient support to debate the options, and training on SDM consultations was required [4]. Interventions to enhance patient involvement in treatment result in increased use of services, more patients receiving their preferred treatment, and better outcomes [60-66]. However, a thin line exists between aiming to modify patients´ desires and beliefs, and intrusively affecting PE which endangers patients´ autonomy [67].

Tools and techniques for a patient-centered approach

These include patient-centered communication, patient education and counseling, management reasoning, and nudging. Patient-centered communication predicted the patient´s continuous adherence 36 months after diagnosis [68]. Management reasoning is premised on negotiating a plan, with ongoing monitoring and modifications of the plan. These necessitate communication abilities, negotiations with patients, and appraisals of the reasoning processes [45]. Justifying the rationale for given management plans commands that clinicians are effective communicators [69], and the race/sex of the patient and surgeon could influence perceptions of such communication [70]. Healthcare professionals might not hold the skills necessary for counseling [71] or lack the confidence to effectively communicate with patients [72]. Improved HCP communication in providing patient counseling reduces the risk of adverse medication problems and readmissions [73]. Management reasoning is whereby clinicians combine clinical data medical knowledge, and patient preferences to suggest management decisions for individual patients [45]. Nudge acts by modifying the architecture of choice, using techniques to encourage people to modify their behavior by employing gentleness rather than coercion [74]. Healthcare professionals need to furnish patients with clear and detailed numerical risk information and clarify how personalized side-effect risks are assessed [39]. The extent of knowledge of and use of such techniques by the treatment teams with our patients is not entirely clear.

This study has limitations. Retrospective interrogation of data has its inherent limitations. It would have been beneficial to interview our cases and receive their perspectives on their decision-making. For future research, we agree with others [75], about the limited appraisals of the reasons why and how patients decide between various treatments, and assessments of patients' views before and after a given choice. Future research should also examine the impact of potential risks on quality of life compared to the oncological outcomes of treatment modalities to undercover patients´ treatment choices and processes underlying treatment decisions.

Selection of guideline-concordant care treatment preferences by patients involves multi-layered complex intellectual and cognitive processes. Patients and the treatment teams need to have the capacity and requisite knowledge and skills to reach a 'wise' guideline-concordant care treatment preference jointly. Patients´ unwise treatment preferences could lead to suboptimal outcomes, in the case of our patients, tumor recurrence.

What is known about this topic

- Ethical dilemmas in patient treatment preferences highlight the pivotal role of patient autonomy in healthcare decision-making;

- Ethical challenges emerge in effectively communicating the risks and outcomes of non-guideline-concordant care choices, requiring clinicians to maintain truthfulness while respecting patient autonomy;

- The role of shared decision-making has not yet been described in the management of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), where there are rapidly developing treatment options and an expanding evidence base.

What this study adds

- Comprehensive understanding of the process of shared decision-making for renal cell carcinoma and the effect on patient adherence to the recommended plans and guideline-concordant care choices;

- Detailed description of the available tools that healthcare professionals can use to assist patients in making 'wise' treatment choices, and avoiding 'unwise' choices;

- A deeper understanding of the factors at play in patient decision-making, advocating for adherence to established guidelines to maximize treatment effectiveness and patient well-being; it underscores the significance of collaborative decision-making between patients and their treatment teams, highlighting the need for both parties to possess the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities for informed choices that are aligned with guidelines.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conceptualization: Khalid Al Rumaihi and Walid El Ansari. Methodology: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil, Walid El Ansari and Alaeddin Badawi. Validation: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil, Nagy Younes and Walid El Ansari. Formal analysis: Walid El Ansari. Investigation: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil and Ali Barah. Resources: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil. Data curation: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil and Walid El Ansari. Writing-original draft preparation: Walid El Ansari, and Ibrahim Adnan Khalil. Writing-review and editing: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil and Walid El Ansari. Visualization: Nagy Younes. Supervision: Khalid Al Rumaihi. Project administration: Ibrahim Adnan Khalil and Walid El Ansari. All the authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

The authors thank the patients involved in this report.

Table 1: patient demographics, MDT plan, original tumor characteristics, and cryoablation details

Table 2: tumor recurrence characteristics

Figure 1: renal masses of three patients by contrasted CT scan; patient 1 (A, B) central right renal upper to mid pole solid lesion (4 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) heterogeneous enhancing exophytic mass lesion arising from the mid pole posterior cortex of right kidney, protruding into right middle lobe calyx (5.4 x 4.8 x 4 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F): completely endophytic heterogeneous enhancing lesion arising from lower pole of right kidney (2.5 x 3 x 3 cm, yellow arrows)

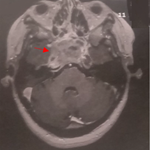

Figure 2: recurrence of renal masses of three patients posts cryoablation; patient 1 (A, B) MRI with recurrence at tumor bed (27 x 18 mm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) CT scan showing slightly cystic hypoechoic focus posterior to right kidney, suggestive of tumor recurrence (3.6 x 2.9 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F) MRI showing focal heterogeneous lesion abutting the renal sinus fat, suggestive of tumor recurrence (18 mm, yellow arrows)

- Malloy-Weir LJ, Schwartz L, Yost J, McKibbon KA. Empirical relationships between numeracy and treatment decision making: A scoping review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 Mar 1;99(3):310-25. PubMed | Google Scholar

- DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002 Sep 1;40(9):794-811. PubMed | Google Scholar

- James JT. Abandon Informed Consent in Favor of Probability-Based, Shared Decision-Making Following the Wishes of a Reasonable Person. J Patient Exp. 2022 Jun;9:23743735221106599. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Peters LJ, Stubenrouch FE, Thijs JB, Klemm PL, Balm R, Ubbink DT. Predictors of the Level of Shared Decision Making in Vascular Surgery: A Cross Sectional Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Jul 1;64(1):65-72. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bartlett Ellis RJ, Carmon AF, Pike C. A review of immediacy and implications for provider-patient relationships to support medication management. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:9-18. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Oct 1;61(10):1042-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Sherbourne CD et al. Primary care patients' involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care. 2006 May 1;44(5):398-405. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Dyer C. Reforms to mental health laws will prioritise care and patient choice. BMJ. 2022;377:o1194. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Peahl AF, Turrentine M, Barfield W, Blackwell SC, Zahn CM. Michigan Plan for Appropriate Tai-lored Healthcare in Pregnancy Prenatal Care Recommendations: A Practical Guide for Maternity Care Clinicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2022 Jul 1;31(7):917-25. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Roe AK, Eppler SL, Kakar S, Akelman E, Got CJ, Blazar PE et al. Do Patients Want to be Involved in Their Carpal Tunnel Surgery Decisions? A Multicenter Study. J Hand Surg Am. 2023 Nov 1;48(11):1162-e1. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Alcorn SR, Corbin KS, Shumway DA. Integrating the Patient's Voice in Toxicity Reporting and Treatment Decisions for Breast Radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2022 Jul 1;32(3):207-220. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Brennen R, Lin KY, Denehy L, Soh SE, Frawley H. Patient and clinician perspectives of pelvic floor dysfunction after gynaecological cancer. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2022 May 24;41:101007. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fraser S. Concordance, compliance, preference or adherence. Patient Prefer Adher. 2010;4:95-96. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Campbell SC, Clark PE, Chang SS, Karam JA, Souter L, Uzzo RG. Renal Mass and Localized Renal Cancer: Evaluation, Management, and Follow-Up: AUA Guideline: Part I J Urol. 2021 Aug;206(2):199-208. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Higgins T, Larson E, Schnall R. Unraveling the meaning of patient engagement: A concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Jan 1;100(1):30-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010 Oct 14;341:c5146. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bai X, Tsiatis AA, Lu W, Song R. Optimal treatment regimes for survival endpoints using a locally-efficient doubly-robust estimator from a classification perspective. Lifetime Data Anal. 2017 Oct;23:585-604. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Gaffney HJ, Hamiduzzaman M. Factors that influence older patients' participation in clinical communication within developed country hospitals and GP clinics: A systematic review of current literature. PLoS One. 2022 Jun 27;17(6):e0269840. PubMed | Google Scholar

- LeRouge C, Durneva P, Lyon V, Thompson M. Health Consumer Engagement, Enablement, and Empowerment in Smartphone-Enabled Home-Based Diagnostic Testing for Viral Infections: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022 Jun 30;10(6):e34685. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Siminerio L. Models for diabetes education. In: Weinger K, Carver CA, editors. Contemporary Diabetes: Educating Your Patients with Diabetes. Berlin: Springer; 2009:29-43. Google Scholar

- Caputo PA, Zargar H, Ramirez D, Andrade HS, Akca O, Gao T et al. Cryoablation versus Partial Nephrectomy for Clinical T1b Renal Tumors: A Matched Group Comparative Analysis. Eur Urol. 2017 Jan 1;71(1):111-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Curtis C, Fatoki O, McGuire E, Cullen A. Moving From 'Best Interests' to 'Will and Preference': A Study of Doctors' Level of Knowledge Relating to the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015. Ir Med J. 2022 Apr 29;115(4):585. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Collins S. Ethics of care and statutory social work in the UK: Critical perspectives and strengths. Practice. 2018 Jan 1;30(1):3-18. Google Scholar

- Christman J. Relational autonomy and the social dynamics of paternalism. Ethic Theory Moral Prac. 2014 Jun;17:369-82. Google Scholar

- Goggins KM, Wallston KA, Nwosu S, Schildcrout JS, Castel L, Kripalani S. Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS). Health literacy, numeracy, and other characteristics associated with hospitalized patients' preferences for involvement in decision making. J Health Commun. 2014 Oct 14;19(sup2):29-43. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Thorne S, Oliffe JL, Stajduhar KI. Communicating shared decision-making: cancer patient perspectives. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 Mar 1;90(3):291-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Thorne S, Hislop TG, Kim-Sing C, Oglov V, Oliffe JL, Stajduhar KI. Changing communication needs and preferences across the cancer care trajectory: insights from the patient perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2014 Apr;22(4):1009-15. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Swainston K, Campbell C, van Wersch A, Durning P. Treatment decision making in breast cancer: a longitudinal exploration of women's experiences. Br J Health Psychol. 2012 Feb;17(1):155-70. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mendick N, Young B, Holcombe C, Salmon P. The ethics of responsibility and ownership in decision-making about treatment for breast cancer: triangulation of consultation with patient and surgeon perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jun 1;70(12):1904-11. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mendick N, Young B, Holcombe C, Salmon P. The 'information spectrum': a qualitative study of how breast cancer surgeons give information and of how their patients experience it. Psychooncology. 2013 Oct;22(10):2364-71. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Salmon P, Hill J, Ward J, Gravenhorst K, Eden T, Young B. Faith and protection: the construction of hope by parents of children with leukemia and their oncologists. Oncologist. 2012 Mar 1;17(3):398-404. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Salmon P, Young B. A new paradigm for clinical communication: critical review of literature in cancer care. Med Educ. 2017 Mar;51(3):258-68. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Taylor C, Finnegan-John J, Green JS. "No decision about me without me" in the context of cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Oct 24;14:488. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mottet NP, Cornford P, Van den Bergh RC, Briers E, De Santis M, Fanti S et al. EAU Guidelines Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam. European Association of Urology. 2022:1-37.

- Deng W, Chen L, Wang Y, Liu X, Wang G, Liu W et al. Cryoablation versus Partial Nephrectomy for Clinical Stage T1 Renal Masses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2019;10(5):1226. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Jun;20(6):531-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fazeli S, Snyder BS, Gareen IF, Lehman CD, Khan SA, Romanoff J et al. Association Between Surgery Preference and Receipt in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ After Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An Ancillary Study of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E4112). JAMA Netw Open. 2022 May 2;5(5):e2210331. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Vromans RD, Tillier CN, Pauws SC, van der Poel HG, van de Poll-Franse LV, Krahmer EJ. Communication, perception, and use of personalized side-effect risks in prostate cancer treatment-decision making: An observational and interview study. Patient Educ Couns. 2022 Aug 1;105(8):2731-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- El Ansari W, Phillips CJ. The costs and benefits to participants in community partnerships: a paradox? Health Promot Pract. 2004 Jan;5(1):35-48. Google Scholar

- Blau PM. Exchange and Power in Social Life. 1964, New York: Wiley.

- Zargar H, Atwell TD, Cadeddu JA, de la Rosette JJ, Janetschek G, Kaouk JH et al. Cryoablation for Small Renal Masses: Selection Criteria, Com-plications, and Functional and Oncologic Results. Eur Urol. 2016 Jan 1;69(1):116-28. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Pecoraro A, Palumbo C, Knipper S, Mistretta FA, Tian Z, Shariat SF et al. Cryoablation Predisposes to Higher Cancer Specific Mortality Relative to Partial Nephrectomy in Patients with Nonmetastatic pT1b Kidney Cancer. J Urol. 2019 Dec;202(6):1120-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1981 Jun 6;282(6279):1847. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Cook DA, Durning SJ, Sherbino J, Gruppen LD. Management Reasoning: Implications for Health Professions Educators and a Research Agenda. Acad Med. 2019 Sep 1;94(9):1310-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Askelin B, Hind A, Paterson C. Exploring the impact of uro-oncology multidisciplinary team meetings on patient outcomes: A systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021 Oct 1;54:102032. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, Corcoran N, Tran B, Bowden P et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Jan 1;42:56-72. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R, Griffith C, Trevatt P, Richards M et al. Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence? BMJ. 2010; 340:c951. Google Scholar

- Kiltie AE, Southby R, LeMonnier K, Binnee J, Niederer J, Kartsonaki C et al. High Levels of Patient Satisfaction in Joint Uro-oncology Clinics to Assist Patient Choice in Early Prostate Cancer and Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2018 Apr;30(4):e39. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Jalil R, Ahmed M, Green JS, Sevdalis N. Factors that can make an impact on decision-making and decision implementation in cancer multidisciplinary teams: an interview study of the provider perspective. Int J Surg. 2013 Jun 1;11(5):389-94. PubMed | Google Scholar

- NICE. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management 2014.

- NICE. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management 2015.

- Nayak JG, Hartzler AL, Macleod LC, Izard JP, Dalkin BM, Gore JL. Relevance of graph literacy in the development of patient-centered communication tools. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 Mar 1;99(3):448-54. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001 Jul 18.

- Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Genuth S. Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Apr 19;154(8):554-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Patients' preferences matter: stop the silent misdiagnosis. King's Fund; 2012.

- Wang R, Yao C, Hung SH, Meyers L, Sutherland JM, Karimuddin A et al. Preparing for colorectal surgery: a qualitative study of experiences and preferences of patients in Western Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Jun 1;22(1):730. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ferreira V, Agnihotram RV, Bergdahl A, van Rooijen SJ, Awasthi R, Carli F et al. Maximizing patient adherence to prehabilitation: what do the patients say? Support Care Cancer. 2018 Aug;26:2717-23. Google Scholar

- Sosnowski R, Kamecki H, Joniau S, Walz J, Dowling J, Behrendt M et al. Uro-oncology in the era of social distancing: the principles of patient-centered online consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cent European J Urol. 2020;73(3):260. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, Tang L, Katon W, Hitchcock P et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006 Feb 1;46(1):14-22. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;189(6):484-93. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Gulliver A, Clack D, Kljakovic M, Wells L. Models in the delivery of depression care: a systematic review of randomised and controlled intervention trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:25. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, Wells KB. Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Med Care. 2001 Sep 1;39(9):934-44. Google Scholar

- Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Hay J, Zhang L, Tang L, Green JM et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care in addressing depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Nov;61(11):1112-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Swanson KA, Bastani R, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Ford DE. Effect of mental health care and shared decision making on patient satisfaction in a community sample of patients with depression. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Aug;64(4):416-30. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002 Dec 11;288(22):2836-45. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Reach G. Patient education, nudge, and manipulation: defining the ethical conditions of the per-son-centered model of care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016 Apr 4;10:459-68. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Liu Y, Malin JL, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC. Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: the role of provider-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 Feb;137:829-36. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Schumm MA, Ohev-Shalom R, Nguyen DT, Kim J, Tseng CH, Zanocco KA. Measuring patient perceptions of surgeon communication performance in the treatment of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer using the communication assessment tool. Surgery. 2021 Feb 1;169(2):282-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Tran TB, Raoof M, Melstrom L, Kyulo N, Shaikh Z, Jones VC et al. Racial and Ethnic Bias Impact Perceptions of Surgeon Communication. Ann Surg. 2021 Oct 1;274(4):597-604. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Yoshida A, Nakada H, Inaba A, Takahashi M. Ethical and professional challenges encountered by Japanese healthcare professionals who provide genetic counseling services. J Genet Couns. 2020 Dec;29(6):1004-14. PubMed | Google Scholar

- van der Giessen JAM, Ausems MGEM, van den Muijsenbergh METC, van Dulmen S, Fransen MP. Systematic development of a training program for healthcare professionals to improve communication about breast cancer genetic counseling with low health literate patients. Fam Cancer. 2020 Oct;19(4):281-90. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Spinewine A, Claeys C, Foulon V, Chevalier P. Approaches for improving continuity of care in medication management: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013 Sep 1;25(4):403-17. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2008;293. Google Scholar

- Anandadas CN, Clarke NW, Davidson SE, O'Reilly PH, Logue JP, Gilmore L et al. Early prostate cancer-which treatment do men prefer and why? BJU Int. 2011 Jun;107(11):1762-8. Google Scholar

Search

This article authors

On Pubmed

On Google Scholar

Citation [Download]

Navigate this article

Similar articles in

Key words

Tables and figures

Figure 1: renal masses of three patients by contrasted CT scan; patient 1 (A, B) central right renal upper to mid pole solid lesion (4 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) heterogeneous enhancing exophytic mass lesion arising from the mid pole posterior cortex of right kidney, protruding into right middle lobe calyx (5.4 x 4.8 x 4 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F): completely endophytic heterogeneous enhancing lesion arising from lower pole of right kidney (2.5 x 3 x 3 cm, yellow arrows)

Figure 1: renal masses of three patients by contrasted CT scan; patient 1 (A, B) central right renal upper to mid pole solid lesion (4 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) heterogeneous enhancing exophytic mass lesion arising from the mid pole posterior cortex of right kidney, protruding into right middle lobe calyx (5.4 x 4.8 x 4 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F): completely endophytic heterogeneous enhancing lesion arising from lower pole of right kidney (2.5 x 3 x 3 cm, yellow arrows)

Figure 2: recurrence of renal masses of three patients posts cryoablation; patient 1 (A, B) MRI with recurrence at tumor bed (27 x 18 mm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) CT scan showing slightly cystic hypoechoic focus posterior to right kidney, suggestive of tumor recurrence (3.6 x 2.9 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F) MRI showing focal hetero-genous lesion abutting the renal sinus fat, suggestive of tumor recurrence (18 mm, yellow arrows)

Figure 2: recurrence of renal masses of three patients posts cryoablation; patient 1 (A, B) MRI with recurrence at tumor bed (27 x 18 mm, red arrows); patient 2 (C, D) CT scan showing slightly cystic hypoechoic focus posterior to right kidney, suggestive of tumor recurrence (3.6 x 2.9 cm, blue arrows); patient 3 (E, F) MRI showing focal hetero-genous lesion abutting the renal sinus fat, suggestive of tumor recurrence (18 mm, yellow arrows)